Editor’s Note: This article is a narrative reconstruction based on court documents, news reports from the time, government documents, and recent interviews with eyewitnesses and other Shreveport locals.

All direct quotes come from these sources.

This article also contains expandable liner notes with additional context for this story. To view the notes, simply click on the arrows to expand.

***

Part I

This all started around 9:30 pm on a balmy late summer night, when two white girls drove to the Sack & Pack grocery store. Cynthia Johnson, the blonde, was in the driver’s seat and Tamala Vergo, her brunette counterpart, was riding shotgun. Vergo was only 17 years old.

Johnson parked in one of the outermost spots and left the engine running.

“Got any rock?” she said.

A few men approached — all young, all Black. They’d been hanging outside of the Sack & Pack, which backed up to A.B. Palmer Park, for hours already. Emboldened by a few too many swigs of whiskey, one of them leaned down, scooped up a few pieces of gravel, and handed them to Johnson.

Meanwhile, on the passenger’s side, a teenage boy gave Vergo a small cellophane bag. She inspected it, then passed it to Johnson. Johnson shook her head and handed it back.

A neighborhood dealer named Hot Rod came along. “You girls better get your asses out of here,” he told them.

This was Shreveport, Louisiana in 1988. Johnson and Vergo had driven to a low-income, predominantly Black neighborhood called Cedar Grove, where it was notoriously easy to score drugs. Between layoffs at the AT&T plant and the oil bust — two of the main industries in town — unemployment was high, and Black men were especially hard hit. A.B. Palmer Park got progressively more crowded with guys killing time.

The park is along a busy street, Line Avenue, but otherwise surrounded by small single-family homes where people sit on their porches when the weather is nice. There’s a baseball diamond and basketball courts often crowded with pickup games.

After games, guys could walk directly from the courts to the Sack & Pack for something cold to drink. The store was something of a neighborhood institution. Somewhere between a 7-11 and a big-box grocery store, the Sack & Pack had a full butcher shop and an assortment of other food and household items. It offered check cashing and interest-free credit accounts for the folks who couldn’t afford groceries until payday. It was even one of the few shops in town that still delivered groceries, in a little makeshift delivery truck.

All this to say, it was a normal Tuesday night for A.B Palmer Park and the Sack & Pack — except for the two white girls who pulled in.

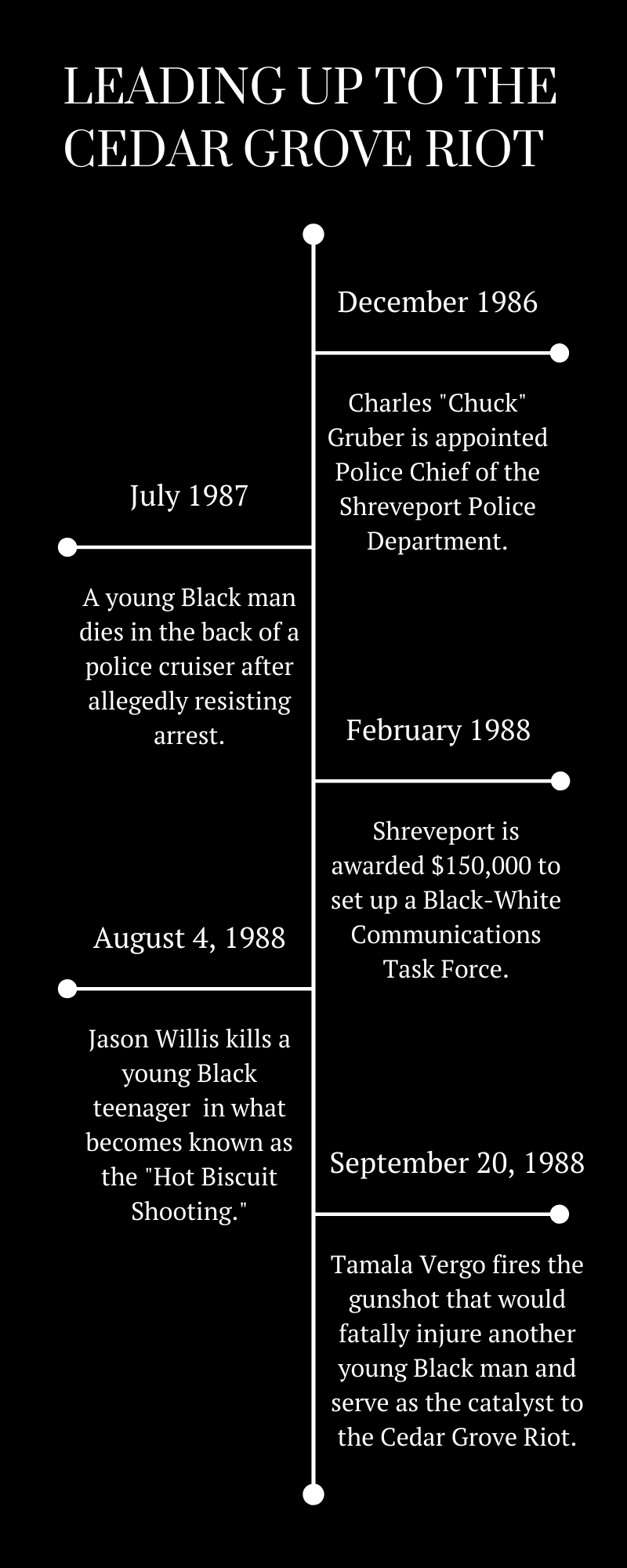

Without warning, Johnson threw the car in reverse. As they drifted back, the alternator light flashed on the dashboard; the car, a 1975 Ford Grenada, stalled. The teenage boy standing on the passenger’s side reached in the window to snatch the bag back from Vergo. Later, she would accuse him of stealing her necklace.

He’d taken a few steps away from the car before someone shouted: “The bitch has a gun!”

Sure enough, there was a chrome-plated revolver in Vergo’s hand, perched between the passenger-side window and the car’s side mirror.

In a split second, half a dozen rounds were fired off. No one agrees where they came from, but the crowd of about 40 people scattered like mercury from a shattered thermometer. Some ducked behind bushes along the side of the store. Others sprinted across the park.

David McKinney, a 20-year-old who was hanging at the park with some friends, rushed toward first base. He was looking back over his shoulder to see where the shots were coming from when everything went black.

***

Part II

Two years earlier, Mayor John Hussey tasked an out-of-towner named Charles “Chuck” Gruber with cleaning up the Shreveport Police Department. Racism and corruption had plagued the department for decades. White supremacists in the force operated with near-impunity, often targeting majority-Black neighborhoods or Black-owned businesses just for the hell of it.

At the time, folks in Shreveport didn’t take well to outsiders, and Gruber was no exception. As a 39-year-old reformer from Illinois, Gruber was the first-ever non-Louisiana-native appointed to the position of police chief. He brought with him his community policing philosophy. He prioritized strengthening the relationship between police and the (often cop-phobic) people they were sworn to protect. The whole thing felt like a slap in the face to the good ol’ boys who had come up under the guns-blazing, arrest-now-ask-questions-later method of policing that had defined the Shreveport Police Department through much of the 20th century. The epithet “Yankee” followed Gruber like a stench.

But Gruber didn’t worry much about popularity. He ousted dozens of high ranking officers who he didn’t think were up to snuff. He prohibited his men from wearing rebel flag pins on their uniforms. He infamously wrestled one of his own captains to the ground and arrested him for showing up to work drunk. Through mandatory continuing education programs, he slowly tried to professionalize the department.

The first real test of Gruber’s leadership came about a year before the riot. Patrol officers arrested a young Black man found wandering the streets of Shreveport, naked, babbling incoherently. This was long before the days of body cameras, but the man allegedly resisted arrest. He died just a few minutes after the officers finally forced him into the backseat of their police cruiser.

Witnesses described the incident as extreme police brutality, and everyone waited with skepticism to see how Gruber would respond.

Gruber assured Black community leaders that the department would conduct a full investigation. He also requested an independent investigation by the FBI. In the end, the investigations concluded that the man was a drug user and had died of cardiac arrest through no fault of the arresting officers. The community accepted the findings.

About six months later, Shreveport was awarded $150,000 to set up a Black-White Communications Task Force. The group was given the not-too-specific mandate of improving race relations in a highly segregated city that was on pace to become majority Black by 2000. It was a noble cause, but things quickly derailed when the board hired a local attorney named Frances “Tutu” Baker as the task force’s executive director.

When Baker was hired, the task force chairman resigned in protest. The chairman, Lydia Jackson, was the daughter of a legendary local civil rights leader and state legislator. As the de facto spokesman of the group, Jackson couldn’t support Baker running the day-to-day operations. She believed Baker didn’t have the necessary experience navigating the complex world of race relations.

Four Black and two white board members resigned alongside Jackson. They said there was a deep divide between the task force’s Black and white members and that the white members weren’t willing to work within the Black cultural framework. In a statement explaining their grievances, they said there was a “subtle intolerance” toward the Black members who tried to educate them.

“According to some white board members, no black ever quite measures up to their ‘objective’ prerequisites for black participation,” the statement read. “Some of us are too confrontational; others are not mainstream. We sound too black to be countenanced or not black enough to be authentic. For whatever reason, we are all unacceptable. It is ludicrous to expect this same group to promote the ‘common good’ of the community in the face of such ignorance and disrespect for 40 percent of the community’s citizenry.”

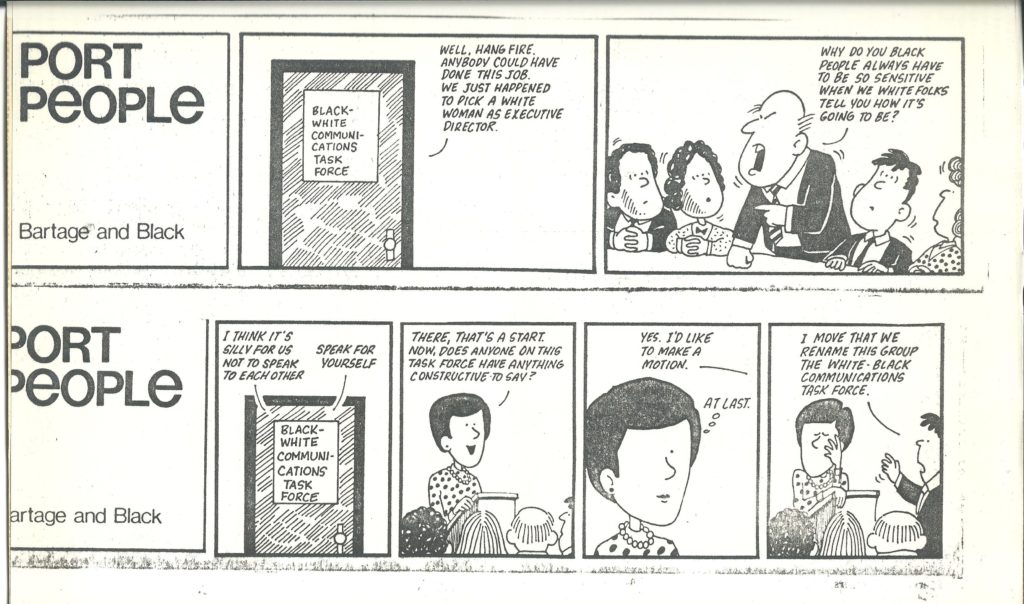

Despite the criticism, Baker continued to lead the task force, though it was seen as less of a task force and more of a “coffee-and-doughnuts club.” The group hosted church mixers with historically Black and majority white congregations. They organized leadership seminars for young Black business owners. Baker even helped create cheeky cartoon strips, intended to kickstart conversations about race, for the Shreveport Journal.

Shreveport Journal

Shreveport Journal

Early in the summer of 1988, a reporter for that same paper sent out a staff-wide memo. “We need to pay attention to the Cedar Grove area,” he wrote, “it’s about to explode.”

Gruber and Baker said they never saw it coming.

***

Part III

On Wednesday, August 3, 1988, Jason Willis and his three cousins Rickey, Bobby, and Stephen spent the evening at an AC/DC concert at the State Fairgrounds. After the concert, they had a few drinks at a local lounge before calling it a night and heading to the Hot Biscuit Restaurant in Cedar Grove for some late-night grub. The Hot Biscuit was an old-school diner, the kind of place that people flooded to after the nearby bars closed. In the early morning hours of August 4, they took their usual seats in the corner booth by the restaurant’s entrance.

Shortly after Jason and the other young white men got their orders, a Black couple entered the restaurant and asked to be seated in the non-smoking section.

“Yes, take those n–––––s over there,” someone from Jason’s group called out as they walked past. (Jason later told police he nor his cousins said anything of that nature.)

The Black couple stopped. They asked to be seated next to Jason’s booth instead. An argument broke out, and the Black man stood at the end of the booth berating the white men. He repeatedly called them “pussies.” Noticing the commotion, a second Black couple joined in. One of the men slapped Jason’s cousin, Stephen, knocking his glasses off his face. The Hot Biscuit’s night manager, a woman named Sandra Kiesler, called the police.

As soon as the police arrived, the two Black couples involved in the argument left.

“It doesn’t seem as if you have a problem now,” the officer told Kiesler.

“I guess not,” Kiesler said.

The officer left without speaking to any of the white men or filing a report.

Less than 10 minutes later, 17-year-old Darren Martin walked into the restaurant with his friends, Willie and Debra.

Kiesler seated them toward the back of the dining room, just about as far away from Jason’s group as she could manage. She told them she was seating them there “because I already had some trouble and I didn’t want any more trouble.”

“That’s fine,” Debra said. “We don’t want no trouble.”

Martin, Willie, and Debra placed their orders, then at some point changed their minds and asked to have their food packed up to go. Meanwhile, Jason slipped past their table on his way to the payphone at the back of the restaurant.

He called home and spoke to his father, James Willis. Jason recounted the argument with the Black couples. He told James the Black men threatened him and he was afraid they were waiting outside for him. James told his son to hold tight — he would be right there.

James loaded his son’s Mossberg 12-gauge pump-action shotgun into his pickup truck and drove two miles to the Hot Biscuit.

Jason and his cousins walked up to the cash register to pay then went to meet James in the parking lot. Martin and his friends walked out of the restaurant with their takeout order shortly afterward.

According to Jason, Martin shuffled up behind him in the parking lot and made a comment — he wasn’t sure what.

“What are you looking at?” Jason said. He noticed that Martin had wrapped some white cloth around the knuckles on his right hand, like a boxer before he puts his gloves on.

“What do you mean? What am I looking at?” Martin replied.

Jason pulled open the passenger door on his father’s truck and swung the shotgun up to his shoulder. He aimed at Martin.

“Leave!” Jason shouted to his cousins.

Martin stepped backward toward Debra’s yellow Chrysler. She and Willie crouched behind the car. Martin reached down to open the trunk.

“Don’t do it,” Debra said. “Don’t open it. There ain’t nothing in there.”

The trunk popped open, Martin reached in, and Jason pulled the trigger. Buckshot pellets ripped through Martin’s chest and collarbone. He crumpled near the left rear wheel of the car.

The only things in the trunk were a spare tire and some dusty old tools. Police pronounced him dead shortly after 3 am.

***

Before the sun rose that morning, Martin’s mother, Ethel, was awakened by one of her other children.

“Momma, wake up. A white man has shot Darren. We have to go ID the body.”

***

Part IV

The Black community was outraged. “Our young people are restless,” said one local Black pastor. “They’re ready for war.” Police and local politicians confirmed their suspicions — the shooting was racially motivated.

To ease the growing tension, the Caddo Parish District Attorney promised to try the case himself. He promised he would get justice for Darren Martin.

On Tuesday, September 20, 1988, the district attorney strode into the Caddo Parish courthouse for a bond hearing for Jason Willis and his father. Police had investigated around-the-clock for nearly a week before arresting Jason, James, and their cousins. They’d fled the scene before officers arrived, and Jason and his father only confessed to the shooting after Rickey told police about their involvement.

Jason was charged with second-degree murder. His father James was charged with accessory after the fact.

That day, the state called Detective Pat McGaha, one of the lead investigators on the case, to testify at the bond hearing. The district attorney was going for $250,000 each. Members of the Willis family waited expectantly in the front row through the entire hearing.

McGaha told the judge everything he knew about the case. He explained key evidence from the local crime lab. He recounted interviews with Willie, Debra, the Willis men, and more.

“Now does anyone — anyone including James Willis, contest the fact that once Jason Willis got the shotgun out of the truck and pointed it at Darren Martin, Darren Martin retreated away from Jason Willis?” the prosecutor asked.

“No sir,” McGaha answered.

“No further questions, your Honor.”

As McGaha left the stand, two of the women seated with the Willis family hissed at him: “kisses, kisses, n–––––s, you n––––r lover.”

McGaha went back to work as usual that afternoon. He was a veteran cop who was born and raised in Cedar Grove. He cruised the cracked streets of Cedar Grove as a young patrol officer. He’d watched the neighborhood shift away from its white lower-middle-class roots and become steadily browner over decades. Racist comments from folks like the Willis’ didn’t rattle him anymore.

But around 11:00 pm, he got a call that did. It was an officer requesting backup at 7912 Line Avenue. McGaha knew the address immediately — it was a Cedar Grove convenience store his friend, Sam Digilormo, owned.

It was Sam’s Sack & Pack.

***

Part V

After the car stalled out and David McKinney fell face down on the baseball diamond at A.B. Palmer Park, Cynthia Johnson and Tamala Vergo ran inside Digilormo’s store.

“Call the police!” they said to the cashier. “They’re shooting at us!”

The man stepped out from behind the cash register and headed toward the back of the store. He was going to ask Digilormo what to do when four or five Black guys poked their head in the door.

“We want them two damn trash came running in — white girl[s] — them damn white trash that come running in here,” they said. “They killed one of [our] best friends.”

The cashier paused. “You all got a gun?” he asked Johnson and Vergo.

“No,” they assured him.

Digilormo called the police while the girls went back to the bathroom. Vergo, the triggerman, stashed the revolver in the toilet tank.

When emergency responders arrived, the crowd had already grown to include hundreds of people. Lots of them had watched the five o’clock news earlier, which covered the Hot Biscuit hearing in excruciating detail. Chants of “Remember the Hot Biscuit!” rippled through the crowd.

Paramedics found McKinney with no pulse or respiration. He was hit in the back of the head.

Inside the store, a couple of officers interviewed the young women.

“Where is the gun?” a sergeant asked.

“I didn’t have a gun,” Vergo said.

He pulled Johnson — who had just been the driver — aside, out of Vergo’s earshot.

“Where’s the gun?” the sergeant repeated. “You know, you’re going to face a murder rap with her. This guy is not going to make it out here.”

Johnson started to cry. “Well, she went in the bathroom,” she said.

A few minutes later the sergeant emerged from the restroom with a wet .38 Smith and Wesson hooked over his finger. He left the gun to dry on a table while he went out to the parking lot to clear the crowd. It took nearly an hour for police to pull a paddy wagon up to the door. Vergo and Johnson darted out of the Sack & Pack, heads down and handcuffed, dodging the bottles being thrown in their direction. Glass shattered at their feet; gunshots pierced the air.

KTBS 3

KTBS 3

When Vergo and Johnson were finally on their way downtown for processing, the crowd shifted their attention elsewhere. Chief Gruber was hit in the leg with a brick. One man, clearly intoxicated, staggered up to a young newspaper reporter and pointed a gun at his head. Someone lit a sedan and a television news truck on fire.

Gruber called off the canine unit and sent for the department’s tactical gear. The neighborhood vibrated with tension, and he knew what angry dogs would look like to the Black community. It would only escalate the hysteria and make it more dangerous for his officers. If someone attacks a police officer, he thought, this situation is going to get a lot worse for everyone.

But the gear was in a closet at the downtown police station, and it had been untouched for years. It was starting to disintegrate.

Unexpectedly, Gruber called his men off. His officers reluctantly complied, while the unarmed firemen at the scene ran for cover. Gruber cordoned off about seven blocks, then 30 blocks of Cedar Grove in a last-ditch effort to deescalate the situation. He set up a command post just outside of the neighborhood. People from the crowd looted Digilormo’s store and the liquor store next door, then set the Sack & Pack ablaze. It started as a small fire, but when the flames reached a shelf full of fireworks, the entire building turned into an inferno. You could smell the smoke from Gruber’s outpost.

By 3 a.m., the Sack & Pack was gone.

***

Part VI

As the sun rose, it was all over. A handful of people were arrested at the riot, but no one else was significantly injured. Shreveport, a city of about 200,000 people in northern Louisiana, garnered national attention for a week or so. A few of the news crews returned when Vergo was sentenced to 10 years for manslaughter, a lesser charge than the second-degree murder the DA was going for. Johnson was acquitted.

“I feel bad that a life was taken and I have problems with that, and I always will,” Vergo told the judge at her sentencing. “But sir, I was in fear of my life.”

Jason Willis was also convicted of the lesser charge of manslaughter in the Hot Biscuit case. Jurors said the state failed to prove that Jason intended to kill Darren Martin. He was sentenced to 10 years and six months in prison without the possibility of parole.

Within weeks of the riot, Mayor Hussey convened a Biracial Commission to study the systemic racism in Shreveport. He appointed Jackson and one of the other former Black-White Communications Task Force members to the commission. A year later, the group produced a 64-page list of recommendations. Most notably, they suggested electing or appointing more Black officials, hiring more Black police officers, and coordinating economic development efforts like job training programs and minority contractor incentives.

“No report of a committee can wipe out centuries of distrust between the races,” the report warns. “No recommendations, no matter how brilliant or practical, can make easy the gargantuan task of changing the social, political, and economic behavior of individuals. All we can do is hold up a compass to the community and point to the direction we should travel.”

Jackson eventually went on to become a state senator.

There were mixed reactions to Gruber’s hands-off approach to the riot. Some called it negligence — like Digilormo and the liquor store owner, who sued the city over the loss of their buildings — but the Black community overwhelmingly supported his decision. The court ruled that Gruber acted lawfully, in accordance with the department’s policy to prioritize human safety over property. “The Yankee” returned to Illinois in 1990 and went on to have a long career in law enforcement reform. But before he left Shreveport, Gruber helped to start a new community policing center in Cedar Grove. It sits on the northeast corner of A.B. Palmer Park, right about where the Sack & Pack used to be.

***

The Cedar Grove riot was a flashpoint in Shreveport’s history, but it was hardly the end of the city’s racial tension.

October 1988: A white teenager named Todd Spillers is shot by a Black male, allegedly in retaliation for the Hot Biscuit shooting. Police deny that the shooting was racially motivated, and Spillers makes a full recovery.

October 1991: A voter survey by the Shreveport Times finds that then-State Representative and former Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan David Duke is only a few percentage points behind the incumbent in the state’s governor’s race. According to the survey, 58 percent of white voters said they supported Duke.

2000: Shreveport is officially majority-Black, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

2010-2014: Caddo Parish sentences more people to be executed per capita than any other county in the United States (among places where 4+ people were sent to death row). According to a later analysis of Louisiana capital punishment, Black defendants face the death penalty more frequently than white defendants, and a Black man is 30 times more likely to be sentenced to death if his victim was a white woman. A white person has never been executed for killing a Black person in the state’s entire history.

2014: Shreveport’s police department is 40 percent Black, and the city has recently been released from a decades-long federal consent decree to diversify the police department.

January 2018: The New York Times produces a mini-documentary about the battles over Confederate monuments and the movement among athletes to kneel during the national anthem. Shreveport is ground zero for the two controversies.

December 2018: The first majority Black city council is elected, despite the city being “majority-minority” since the turn of the century.

February 2019: A Black man named Anthony Childs is shot by Shreveport police. His crime? Violating the city’s saggy pants ban. According to an analysis by the Shreveport Times, 96 percent of people arrested for violating the saggy pants law were Black men. The city council repealed the law in June.

***

Fact-Checking by: Lydia Belanger

Editing by: Mariana Heredia